What later evolved into the production Matisklo began when we read the testimonies of Primo Levi and Imre Kertész, testimonies of an interminably dark page in European history: the Holocaust. Both of them were survivors of the concentration camps, and they not only wrote about what happened there, but about what it means to testify to something that is so unfathomable, something so dark and deep that it threatens to go beyond language, the most important medium for testimony. More than bearing witness to a specific historical event, the writings of Levi and Kertész testify to what it means to be human – or inhuman.

Levi and Kertész are irrefutably clear. Merciless essayists both, they show us that in the moral sense it is above all grey; they have personally experienced that people do not correspond to what they pretend to be, what they hope to be, and what they perhaps ‘ought to be’. “All of human civilization”, says Kertész, “is based on the tacit consensus that people are not to be reminded that they value their own lives more, far more than all other previously proclaimed values.”

We were convinced of the need to share these insights in an artistic project, but we did not see their texts as material that we wanted to work with ourselves. The idea of staging or turning these testimonies into fiction raised huge questions for us. This is language that strives to be as effective and unambiguous as possible. Juxtaposing our imagination with that seemed misplaced. In the writings of Levi and Kertész, there is little in the way of a dialogical process with the reader. You have to take their words in, as a reader, and consider them.

The poetry of Paul Celan, also a concentration camp survivor, addresses you in a very different way. This is language that does not deal with morality, dehumanization or what has been lost in terms of human dreams and perspectives. Here, what has been lost primarily becomes apparent in the language itself. The world has fallen apart, and language along with it; but the pieces pick themselves up and speak anew.

Paul Celan wrote his poetry from a (certainly not always hopeful) conviction that his poems would wash up on land somewhere as ‘messages in a bottle’. “Poems are en route”, he said in a lecture in Bremen. “They are headed towards. Toward what? Toward something open, inhabitable, an approachable you, perhaps, an approachable reality.… They are the efforts of someone who goes toward language with his very being, stricken by and seeking reality.”

‘An approachable you, an approachable reality.’ Perhaps this is why we felt that Celan addressed us not only as people but as artists. His language contains lacunae and gaps, it is incomplete in a positive way. Celan forces you to use your imagination, to actively be in a memory, to be a witness yourself, as reader. The past has not gone away, it gains a voice through. Through you, it looks at the future, a future even beyond mankind and beyond death.

“There are still songs to sing beyond mankind”, he writes in the poem THREADSUNS from the collection Breathturn into Timestead. It is a declaration of his confidence – not confidence that things will go well for mankind or human nature, or for himself – but confidence that language came before us and also goes far beyond us. The stubbornness of Celan’s poetry lies in the fact that he refuses to speak in ‘this world’. Celan speaks in the world of things, colours, physical and geological processes, gobbling them up, digesting. Often, the subject of his poetry disappears, to be replaced by a dubious ‘you’.

Celan chews words into images like no one else. This is certainly true for Breathturn into Timestead, the collection of poetry we are working with in the first part of the show, in which he constructs scenes with word images.

Landschap met urnwezens.

Gesprekken

van rookmond tot rookmond.

Ze eten:

de gekkenhuistruffel, een stuk

onbegraven poëzie,

vond tong en tand.

Een traan rolt terug in haar oog.

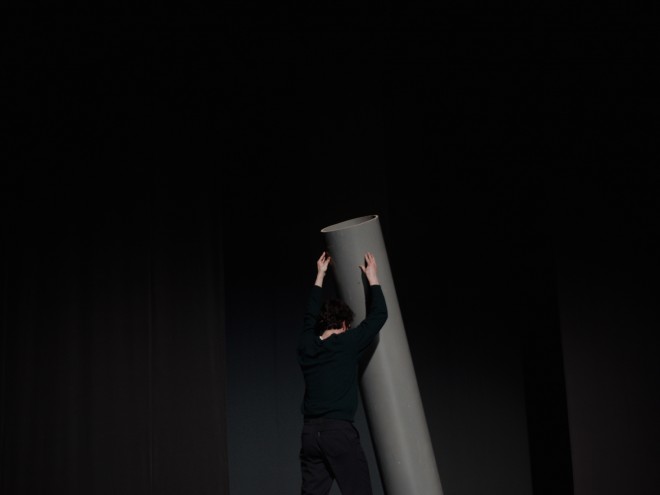

Celan’s language landscapes not only invite us to recite them but to create our own images. We don’t visualize his words, we accept his invitation to imagine more. In Matisklo, split landscapes arising from Celan’s poems come into view. Indecisive places, the nature of which changes according to the beings that visit them and the words that are spoken there. As a result, a forest and a concentration camp can look alike in Matisklo, just as people can ‘scoop out a grave in the sky’, according to Celan’s most famous split image.

Diepindesneeuw,

iepindeeuw,

i-i-e.

In Breathturn into Timestead, language literally becomes matter: words can erode, letters can drift apart. The poems – to translate the previously mentioned ‘difficulty’ of his poetry into the material world – are like shells, but they are palpable. Also like shells are the costumes that Max Pairon made for Matisklo. On the one hand, these are silent figures that seem incapable of speaking a language that we can understand, and on the other hand you can also see them as incarnations of poems. Shells crawling about, where one is only able to surmise the purpose of the chestnut.

In Snow Part, the last collection that Celan compiled himself, something seems to open up. The world seems to have become lighter now that he has decided to join the dead. In the second half of Matisklo, which is devoted to Snow Part, the earlier focus on materiality and texture shifts to the nonvisual: more emphasis is placed on the language and the lighting. Now the costumes reveal hardly any traces of humanity: this is a place where trees and rocks speak with each other. Arrival, origins.

The performance ends with poems from the last cycle of Snow Part. Celan shoots up into the cosmos wielding an incredibly eclectic pallet of words. This is a final gush of language in which he flies away from us with ‘dream propulsion’ through time and space, into the indescribable.

← Back to overview