Bart Meuleman: Ezra, you are the scenographer and lighting designer for Matisklo. Everything that determines what the space looks like is in your hands. What sort of space do you want to create?

Ezra Veldhuis: I don’t know if the spaces or the lighting are ‘in my hands’ in that way. What’s so great about making theatre is that you develop an artistic language as a group, so that everything is in constant dialogue with everything else. That’s a big difference with working autonomously as a visual artist, where I make all the decisions myself. The broad outlines of the design are based on the intuitive mental images of the space that Bosse and I had when reading Paul Celan. When I read his poems, images of places or landscapes often come to mind. We have tried to find ways of making these places possible in the design. For instance, the curtains hanging on stage can be walls or part of a landscape, but they also can simply be curtains from behind which an actor can appear. We are still looking for the best way to design this. Another example is the tubes we are using. They can be chimneys, but also trees.

Bart: As a spectator, will you be able to understand when the meaning of those objects changes? That in other words the places become different?

Ezra: There aren’t any explicit places, it’s constantly shifting. When you read Celan’s poems, one moment you’re more or less in the cosmos and the next you’re in a grey landscape. So you will not see those places explicitly, but they

are touched upon.

Bart: You’ll experience the differences?

Ezra: Yes. It does stay abstract, of course – what we are doing is super abstract. But I hope that you can follow it when the status of a curtain or a tube changes. Sometimes we will use an image from a poem without even reciting that poem in the show. Joeri initially had a series of six poems from the Breathturn anthology (Atemwende, 1967), but now it’s down to only three: the other three have become ‘images’.

Bart: Celan’s poems are about the impossibility of speaking of the Holocaust, because it goes beyond all of our powers of imagination. It’s poetry that is not easily accessible. Do you think it’s your task to help clarify his poetry?

Ezra: I don’t know if we’re actually looking for clarification. But it does have to come across, naturally. Everything – acting, design, costumes, lighting, music – is based on the poems.

Bart: Can you say something about the structure of the show?

Ezra: There are three parts to the show. The first is based on poems from Breathturn (Atemwende, 1967), the second on Threadsuns (Fadensonnen, 1968) and the third on Snow Part (Schneepart, 1971). The first part is the one with something most like a scene, between Geert Belpaeme, in the Wood Man costume (a suit designed by Max Pairon, entirely made of little wooden slats), and Benjamin Cools. In that part we are still in this world, in a woody area or an industrial landscape, whereas in the third part we almost find ourselves already in the Beyond, in an undefined place. When Celan wrote Snow Part, he actually already knew that he was going to commit suicide.

Bart: The lighting also plays a very important role.

Ezra: In the first part, we looked for lighting that emphasizes materiality. And we are indeed in an earthly landscape here. I work with pale pink light and blue light, which very subtly produces two different shadows. As a result, everything becomes wider. In part three, the pink is gone; the only light that remains is what we experience as white. I take out all of the shadows, which normally give us ‘body’. You get a glacial, diffuse kind of light. That way, we end up in an indeterminate space.

Bart: A hereafter?

Ezra: It could be.

Bart: Not the, but a hereafter.

Ezra: In any case, we are not on earth anymore. And in the second part we sometimes try to have the light function autonomously.

Bart: Do you mean a scene in which you only see changes in the lighting and no

characters at all?

Ezra: Yes a real ‘light show’. The light becomes a performer.

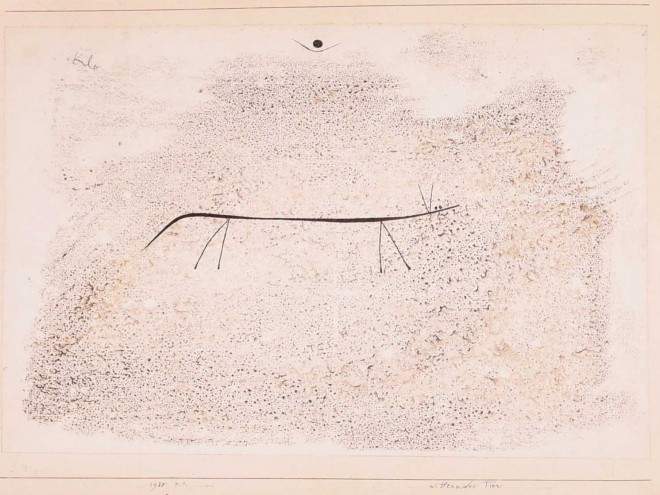

Ezra’s choice of poems:

DAS UMHERGESTOSSENE

Immer-Licht, lehmgelb,

hinter

Planetenhäuptern.

Erfundene

Blicke, Seh-

narben,

ins Raumschiff gekerbt,

betteln um Erden-

münder.

WARUM AUS DEM UNGESCHÖPFTEN,

da’s dich erwartet, am Ende, wieder

hinausstehn? Warum,

Sekundengläubiger, dieser

Wahnsold?

Metallwuchs, Seelenwuchs, Nichtswuchs.

Merkurius als Christ,

ein Weisensteinchen, flußaufwärts,

die Zeichen zuschanden-

gedeutet,

verkohlt, gefault, gewässert,

unoffenbarte, gewisse

Magnalia.

← Back to overview